Mohamed Aden Ali, 11, has been paralysed by polio. Abandoned by his parents, he moves by crawling on two worn kneepads strapped to his thin legs and uses rubber sandals to protect his hands. He is in the stadium in Baidoa, filled with spectators. They came to watch a football match between the teams 'Polio 2000' and 'Polio 2001'. In a place that was a famine epicentre in the 1990s, the match is one of a variety of activities used by immunizers to gain support for the eradication campaign. 'Polio 2001' won the match by one goal.

During a NID, health workers cross the Juba River en route to the village of Aboorrow. The river marks the border between two clans in this part of Somalia. Because communities often only accept vaccine from their own clan members, health workers from one clan must hand over vaccine to their counterparts from a neighbouring clan. Smaller teams then fan out to reach outlying villages. It is a complex operation, but key to reaching Somali children. Vaccinators wear T-shirts and caps to clearly identify themselves as health workers and transport the vaccine in cold-storage boxes to ensure its effectiveness.

An armed guard assists with a vaccination in Bardale. Continuing conflict requires that non-Somalis participating in polio eradication campaigns be accompanied by guards. The security risks are real. In 2001, several international polio workers were held captive for several days following a battle between their guards and militia from another clan

Children of nomads are vaccinated near Aboorrow, where they have come with their families to collect water from the Juba River. Immunizers are keen to reach nomadic families because their way of life can facilitate poliovirus transmission.

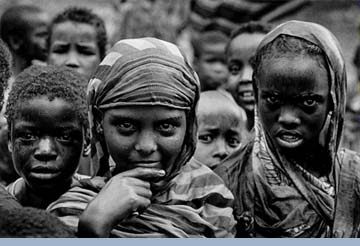

Children in Gof Gudod stand in the rain to watch the vaccinators who have come to their village.